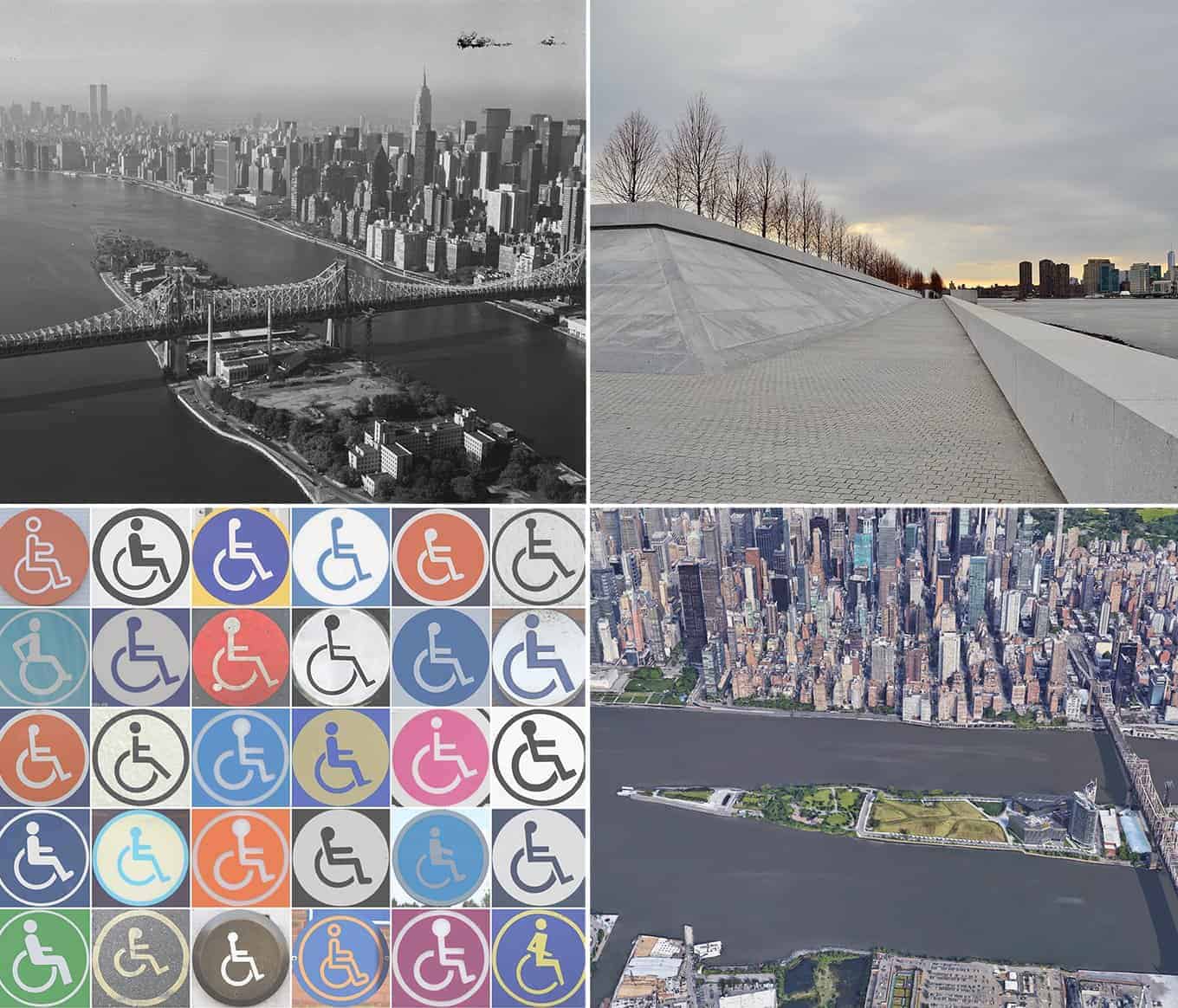

"The news headline was optimistic: “Three ‘Ribbon’ Bike & Pedestrian Bridges For NYC Are More Than A Coronavirus-Concocted Fantasy.” In the early months of the pandemic, city planners added several dozen miles of open streets to encourage socially distanced recreation and transit. But as the article in the Gothamist explained, a group of well-connected transportation engineers was pushing for more ambitious plans, urging the construction of three new bridges for New York City. These would not resemble the traditional “bulky” and “clunky” bridges that for more than a century have carried car traffic through the metropolitan region; these would be comparatively delicate structures dedicated to cyclists and pedestrians — “wispy ribbon bridges crisscrossing the city’s waterways.” One crossing in particular drew the engineers’ attention: the “Queens Ribbon,” a slender, twenty-foot-wide suspension bridge that would span the East River from Long Island City, to Roosevelt Island, to Manhattan.

For months now the design press has been filled with stories about the possibilities of post-pandemic urban planning, envisioning cities where commuters have options beyond overcrowded buses and subways, where streets have fewer cars and more bike and foot traffic. “The first new bridge to Manhattan in decades — one just for cyclists and pedestrians,” is how the New York Times described the proposed Queens Ribbon. Indeed, proponents of “active transportation” — defined as human-powered mobility, chiefly walking and cycling — are hopeful that contingency measures adopted during lockdown will outlast the arrival of coronavirus vaccines. But what is usually missing amidst the growing enthusiasm for non-motorized mobility is any awareness of the ways in which projects like the Queens Ribbon, and more broadly the concept of active transportation itself, can reinforce longstanding forms of exclusion."

Places Journal: Active Exclusion

Too often the concept “active transportation” produces environments that are not fully accessible. The history of Roosevelt Island, named for a disabled president who used a wheelchair, offers lessons at once troubling and hopeful.