Challenges to deliver adequate housing in a sustainable manner touch every corner of the globe, but nowhere is the situation more urgent than in Africa. The UN estimates that 238 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa currently live in slums or informal settlements, a number accounting for well over half of the region’s urban population. At the same time, of the world’s 30 fastest growing cities, 21 are in Africa, with populations set to double by 2035. The continent is in the midst of a housing crisis that is only going to get tougher.

To face this challenge, there is a growing commitment among Sub-Saharan African governments to embark upon mass housing developments. The strategy intends to meet housing demand while also sparking broad economic stimulation by creating jobs during the planning, construction, and procurement of homes. To say this strategy is incomplete understates the case, and there is a compelling argument that it will prove harmful in the long run. But it is not too late to right the ship.

Single-use development brings unintended consequences.

In many ways, Nigeria is a microcosm for what is happening throughout the continent. As part of its 2020 Economic Sustainability Plan, the country pledged to build 300,000 houses, with a proposal to construct 400 units in each local government area (LGA). With an average household size of five people, the proposal entails expanding existing cities by 2,000 inhabitants in every one of the country’s 774 LGAs.

A visit to any Nigerian housing development today makes their unsustainability obvious. These areas have what we’ve identified recently as linear metabolisms, consuming water, food, and building materials while producing pollution, waste, and extreme levels of urban sprawl. This uncontrolled expansion of the urban footprint has placed undue pressures on the basic infrastructure of cities, with Lagos as a key example, which recently declared it would require $5 billion of annual infrastructure spending to keep pace with the projected growth — up from the $3 billion currently budgeted. Needless to say, the upkeep of such developments has presented enormous cost challenges to their administrators.

United Nations reports confirm the consequences across the continent. Only 52% of solid municipal waste in Sub-Saharan Africa gets collected. The global average, by contrast, is 81%, with 99% collected in Australia and New Zealand. This unfortunate reality contributes significantly to local pollution of air, water, and soil, in turn elevating greenhouse gas emissions and contributing to public health challenges.

Worsening the situation is the lack of alternative programming in and around the developments. With office, retail, and recreation facilities located elsewhere, residents are forced to commute long distances. Yet only 18% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have convenient access to public transportation, so practically all of this transportation happens by car. The situation’s environmental consequences are severe, to say nothing of the suffocating traffic congestion with resultant lost wages and wasted space dedicated to parking.

A circular cities framework provides the necessary alternative.

We can reimagine the linear metabolism prevalent in Africa and so many emerging economies around the world with a more resilient, regenerative approach to planning and developing cities. Within Gensler’s circular cities framework, housing developments are designed as self-sustaining communities. The strategy entails repurposing spent resources into renewable energy, an environmentally sustainable approach that also creates profitable knowledge and skills. The investment can then lead to enough commerce to limit or even invert the financial bleeding commonly associated with the housing projects themselves. Governments have conceived housing developments as job creators, but only through the construction phase. By extending the time horizon to include infrastructure support and resource management in the long run, the economic benefits would multiply many times over.

Another way in which a circular framework would benefit African cities is its insistence on true mixed-use development. Housing development must not be done in isolation. It needs to be undertaken alongside workplace, education, retail, hospitality, food and beverage, and medical development. Communities that follow a mixed-use strategy tend to exhibit more stable growth and become destinations where people want to live. In particular, they do a better job of supporting people of all ages. Children benefit from having local schools and parks in which to learn and play, parents benefit from being able to find employment close to home, and grandparents benefit from no longer needing to undertake lengthy trips for medical care.

What building a new circular city looks like in practice.

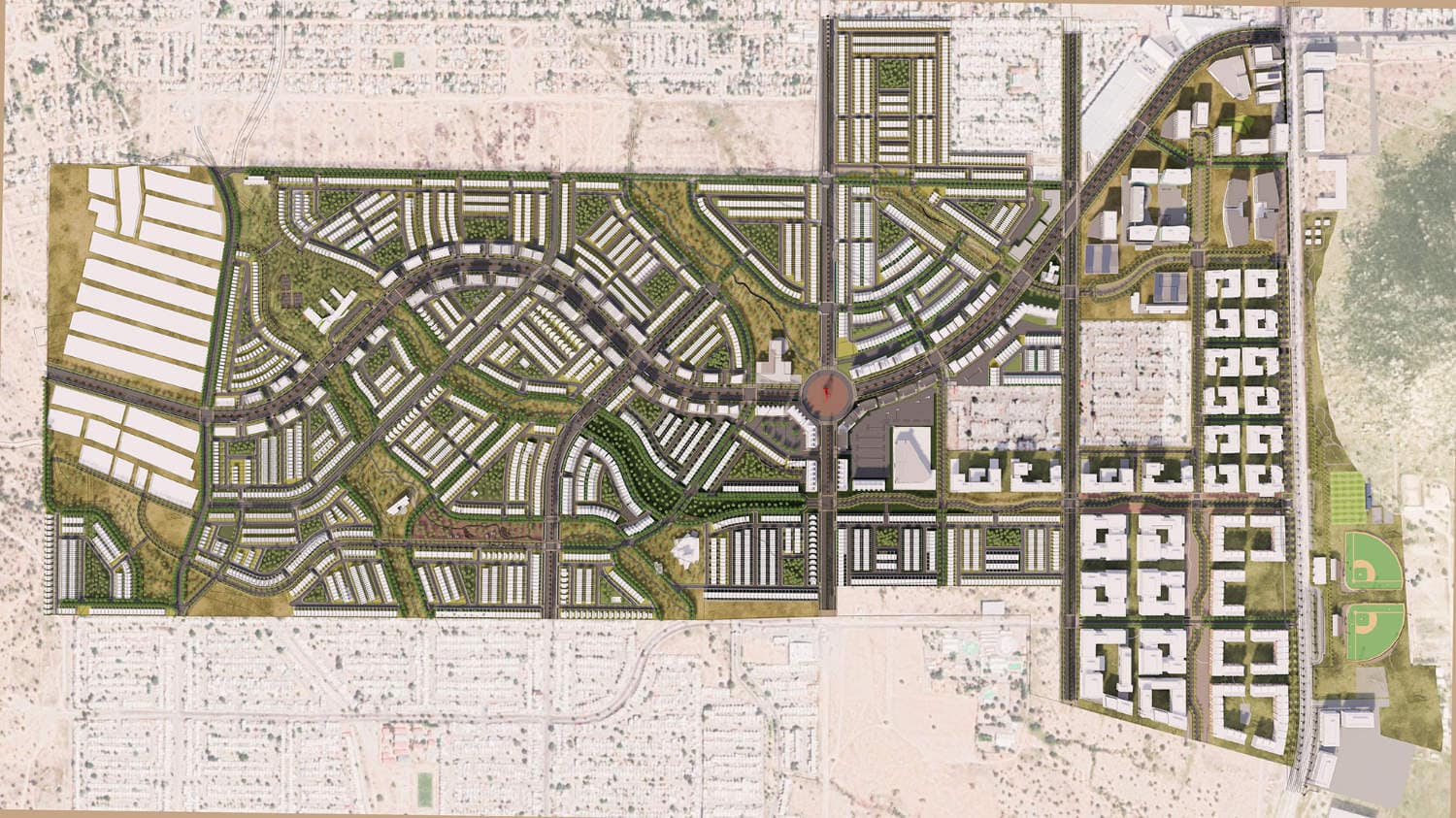

The master plan Gensler created for a 275-hectare site within Hermosillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Sonora, exemplifies what these principles look like in action. Mass housing challenges throughout Latin America mirror those of Africa in many key ways. Among them is a similar tendency with governments to build high numbers of housing units without giving due consideration to other forms of community development. The Hermosur development is markedly different. It is a proper city unto itself, a new centrality in what is already becoming a polycentric city, that promotes sustainable economic growth, inclusiveness, and innovation while meeting high demands for housing.

Hermosur accomplishes this by baking various densities, mobility modes, and anticipated technology evolutions into the master plan. The thrust of the strategy is to give residents a chance to do something meaningful in their lives — to gain employment and build a sense of local community. Alongside new housing are fire stations, churches, markets, cafes, schools, health care centers, and commercial and industrial sectors: indispensable components of a thriving city.

The master plan for Hermosur places it in harmony with nature, emphasizing a walkable pedestrian experience throughout its winding, tree-lined streets and bike paths, which in turn follow the existing network of drainage channels or “arroyos.” It envisions permeable housing perimeters to allow visibility and collective care over the neighborhood for a harmonic coexistence among residents. Intelligent water management bolsters the area’s sustainability; it uses the landscape’s green fingers to form a natural gutter system and preserves the native landscape’s core functions and much of its flora.

With some of the fastest rates of urbanization in the world, African cities hold unbelievable potential. It is well within the power of their governments to create developments with characteristics and benefits similar to Hermosur, given the right mindset and partnerships. We are convinced that African cities are uniquely positioned to be successful in their growth, but that success will not come automatically.

The danger for the continent is the urgency and scale of its need amid a context of economic uncertainty. The best principles for designing genuinely resilient and economically sustainable cities are getting lost in the quest to satisfy ever-increasing demand. For future African cities to be the global magnets and domestic havens they can be, it will be necessary to adhere to those principles and approach mass housing with a regenerative, circular mindset.